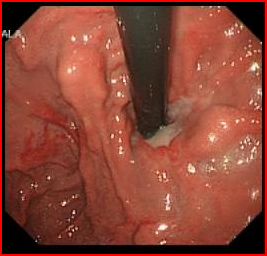

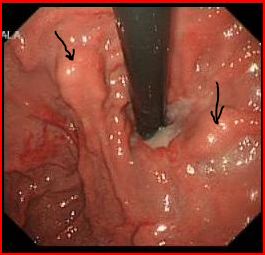

Mr Jacob a 55 year old unemployed man was admitted with haematemesis. His endoscopy showed:

What is the diagnosis?

Gastric varices (GV)

Endoscopically the gastric varices could be tortuous, nodular or timorous. GV lie in the submucosa, deeper than oesophageal varices, and distinguishing GV from gastric rugae may be difficult.

What are the types of gastric varices?

Varices are classified into 2 categories:

- Gastro-oesophageal varices (GOV)- varices extending from the oesophagus into the stomach

- GOV1- extending along the lesser curvature of the stomach (treated as oesophageal varices)

- GOV2- extending along the greater curvature towards the fundus

- Isolated Gastric varices (IGV)- when gastric varices are present in absence of oesophageal varices

- IGV1- located in the gastric fundus

- IGV2- located in the antrum, corpus or pylorus

GOV1, the commonest at 70% of gastric varices, are also known as cardial varices. GOV2 and IGV1, at 21% and 7% of gastric varices, respectively, together referred to as fundal varices (FV).

- GV also may be considered primary or secondary. Primary GV are those present at initial examination or in a patient who has never had sclerotherapy or variceal band ligation. Secondary GV refer to those that develop after endoscopic therapy for oesophageal varices.

What are the causes of gastric varices?

- GV (like oesophageal varices) occur in patients with generalized portal hypertension (PHT) of diverse origins. Gastric varices are more common in patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) and extrahepatic portal vein obstruction.

- IGV also occur in individuals with segmental (left-sided) PHT, arising from pathology of the splenic vein, such as thrombosis or stenosis, often as a sequelae of pancreatic pathology.

Discuss the unique features of gastric varices?

- FV are found in the submucous layer, but not in the lamina propria unlike oesophageal varices. As a result, the risk of bleeding from gastric varices is half that of oesophageal varices. However, when they do bleed, the haemorrhage is more severe leading to higher mortality and transfusion requirements than oesophageal varices.

- It is hard to predict near future rupture of FV on their endoscopic findings, because the so-called red colour sign, which is frequently observed over the surface of oesophageal varices, is rarely observed on the surface of FV.

- Risk factors for gastric variceal bleed include fundal location, large size, red colour sign (rarely), and advanced child stage.

- Bleeding should be considered to have arisen from GV if there is

- Active spurt or ooze,

- Adherent clot,

- Presence of large GV,

- No oesophageal varices, and

- No other source of bleeding evident.

What causes rupture of gastric varices?

Fundal varices form in the submucosa, however they do penetrate through the muscularis mucosae and lamina propria at sites where they protrude into the stomach lumen; these vulnerable positions are where rupture occurs, possibly triggered by a mechanical insult or an ulcer overlying the GV, although this remains unproven.

Is there any role of primary prophylaxis in gastric varices?

- In view of the low incidence of rupture, no prophylactic treatment seems warranted for FV. However, because the mortality of GV haemorrhage is high, it has been suggested that patients at high risk for bleeding should undergo primary prophylactic eradication of the GV. This is not standard accepted practice in most western centres.

- There are no good data regarding the role of beta-blockers in the primary prevention of GV bleeding. However, it seems reasonable to give beta-blockers empirically in primary prevention of GV bleeding, although their value is not proven.

Discuss the management of acute gastric variceal bleeding?

- Pharmacotherapy: There is little data concerning the efficacy of somatostatin or vasopressin or their analogues in the control of acute GV bleeding. However, it is not unreasonable to give these agents empirically in acute GV bleeding, although it is likely that the often voluminous bleeding from GV might not be staved by pharmacologic measures.

- Antibiotics- within 48 hours of an acute variceal bleed, bacterial infection occurs in 20% of cirrhotic patients and is associated with a worsening of prognosis.

- Endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) therapy- This refers to the injection of agents such as histoacryl, or thrombin. EVO has emerged as the initial treatment of choice for acute GV bleeding achieving haemostasis in 90% of cases. Thrombin also has been used to control fundal variceal bleeding with a relatively good success rate of up to 75%.

- Balloon Tamponade- can be used as a stopgap to definitive treatment. The commonly used Sengstaken–Blakemore or Minnesota tubes are not usually efficacious in controlling bleeding from fundal varices, owing to the small volume of the gastric balloon (200 mL). The Linton– Nachlas tube has a 600-mL volume single gastric balloon and seems to be more effective in controlling fundal variceal bleeding in up to 50% of patients, although 20% subsequently will rebleed. It is not infrequent for rebleeding to occur due to inadequate traction, particularly within the first few hours of a variceal bleed.

- TIPS- The current role of TIPS in acute GV bleeding is as second-line rescue therapy when EVO has failed. TIPS can control acute refractory GV bleeding in 90% to 100% of cases. Rebleeding occurs in 10% to 30% of patients within 1 year. EVO is more cost effective than TIPS in acute GV bleed.

- Shunt surgery- second-line treatment of refractory acute GV bleeding.

Discuss the role of sclerotherapy and endoscopic variceal banding (EVL) in acute GV bleed?

Sclerotherapy: Traditional variceal sclerotherapy involves injection of sclerosants such as ethanolamine oleate or absolute alcohol intra- or perivariceally (or both), resulting in endothelial damage and thrombosis of blood and subsequent sclerosis of the varix. It is not appropriate for patients with fundal varices (GOV2 or IGV1) because of the low rate of primary haemostasis and the high rate of rebleeding. This may be because of the high-volume blood flow through GV compared with oesophageal varices, resulting in rapid flushing away of the sclerosant in the bloodstream.

EVL: Some centres have used EVL successfully for GV smaller than 2 cm in diameter. However, not all centres have had good results with EVL of GV, and it can be technically difficult to place a band around GV because of their size and the thick overlying mucosa.

Discuss the secondary prevention of GV?

- The role of beta-blockers and nitrates in secondary prevention of GV bleeding has not been studied extensively.

- EVO is the treatment of choice for secondary eradication of GV.

- TIPS or shunt surgery are other options for secondary prevention.

Discuss histoacryl glue treatment?

Histoacryl is a monomer that rapidly undergoes polymerization on contact with the hydroxyl ions present in water. This changes the liquid to a hard brittle acrylic plastic. This causes plugging and thrombosis of the varices. The patency of the varix is assessed by blunt palpation with a catheter or biopsy forceps and additional glue is injected until the varix is ‘hard’ to palpation. On subsequent endoscopies, the patency of the varix is assessed by either blunt palpation or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). Months after the injection, the mucosa overlying the glue cast sloughs off and the plug is extruded into the stomach.

Histoacryl can be utilized for secondary prevention by repeat injections at 1- to 2-weekly intervals to ensure eradication of the varices. Obliteration is the term used for gastric varices treated by glue rather than eradication, as the varix itself can be visible even when it has been effectively treated. Indeed, the fact that the varix is still present makes assessment of obliteration difficult. Average number of sessions needed to achieve obliteration range from 1 to 3. Once varices are obliterated, some experts inject glue every 6 months.

Complications of histoacryl: Side effects include mild and transient pyrexia and abdominal discomfort. Uncommon side effects caused by histoacryl glue include cerebral, pulmonary, and portal vein embolism, retroperitoneal abscess, splenic infarction, and portal and splenic vein thrombosis. The systemic emboli complications are increased in patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome. These complications can be reduced by avoiding it in patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome and by using no more than 2 mL of injection in a session.

Discuss the management of gastric varices caused by left sided portal hypertension like splenic vein thrombosis?

- Histoacryl is the treatment of choice for acute GV bleed as well as for secondary prevention as in generalised PHT related GV

- TIPS is not an option as only veins draining from spleen have raised pressure.

- Segmental PHT and associated GV are cured effectively by splenectomy or splenic artery embolization or in the case of splenic vein stenosis, by stenting of the splenic vein

Ref