Iron-deficiency anaemia (IDA)

How do you diagnose IDA?

IDA is diagnosed by haemoglobin less than the normal limit for the lab, MCV <76fl and ferritin <15ug/dl. Both microcytosis and hypochromia (MCH) are sensitive indicators of IDA. However they are also present in thalassaemia, sideroblastic anaemia and anaemia of chronic disease.

Ferritin is an acute phase reactant may be elevated, if concurrent inflammation is present. In such cases iron deficiency can be diagnosed by low serum iron and high TIBC or low transferrin saturation. In contrast anaemia of chronic disease has low serum iron and low TIBC with normal transferrin saturation.

How common is IDA?

IDA occurs in 2-5% of adult men and post-menopausal women in the developed world (responsible for 4-13% of GI referrals)

Discuss the causes of IDA?

IDA is often multifactorial

- Common causes- Aspirin/NSAID use, colonic cancer/polyp, gastric cancer, angiodysplasia, IBD, gastric ulcer.

- Uncommon- oesophagitis, oesophageal cancer, water melon stomach, intestinal telangiectasia, small bowel tumours, duodenal polyp, carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater, hookworm

- Malabsorption- Coeliac disease, gastrectomy (partial or total), gut resection or bypass, bacterial overgrowth, Whipple’s disease, lymphagiectasia.

- IDA is very common after either partial or total gastrectomy.

- In patients with recurrent IDA and normal OGD and colonoscopy results, H. pylori should be eradicated if present

Who should be investigated for IDA?

BSG recommends the following groups should be investigated with upper GI endoscopy and Colonoscopy/CT colonography:

- All postmenopausal women and all men with IDA

- All premenopausal women with IDA should be screened for coeliac disease, but other upper and lower GI investigation should be reserved for those aged 50 years or older, those with symptoms suggesting gastrointestinal disease, and those with a strong family history of colorectal cancer.

- Upper and lower GI investigation of IDA in postgastrectomy patients is recommended in those over 50 years of age

- In patients aged >50 or with marked anaemia or a signi?cant family history of colorectal carcinoma, lower GI investigation should still be considered even if coeliac disease is found.

- In patients with iron de?ciency without anaemia, endoscopic investigation rarely detects malignancy. Such investigation should be considered in patients aged >50 after discussing the risk and potential bene?t with them. Only postmenopausal women and men aged >50 years should have GI investigation of iron de?ciency without anaemia. All others should be treated empirically with oral iron replacement for 3 months and investigated if iron de?ciency recurs within the next 12 months.

- Age is the strongest predictor of pathology in patients with IDA, and thus GI investigation is recommended for asymptomatic premenopausal women with IDA aged 50 years or older

- If IDA develops in a patient with treated coeliac disease, upper and lower GI investigation is recommended in those aged >50 in the absence of another obvious cause.

- Colonic investigation in premenopausal women aged <50 years should be reserved for those with colonic symptoms, a strong family history (two affected ?rst-degree relatives or just one ?rst-degree relative affected before the age of 50 years), or persistent IDA after iron supplementation and correction of potential causes of losses (eg, menorrhagia, blood donation and poor diet)

Studies in patients referred to hospital for investigation of their IDA have shown that 5%-15% have a gastrointestinal cancer. However, age is the strongest predictor of pathology in patients with IDA.

Further, although it is convenient to use the term pre-menopausal, it is menstruation which influences the investigative pathway. It is probably wise to fully investigate those premenopausal women who have IDA but no menstruation (e.g. after hysterectomy).

A signi?cant family history of colorectal carcinoma should be sought, that is, one affected ?rst-degree relative <50 years old or two affected ?rst-degree relatives.

Discuss investigations for IDA?

- All patients with IDA should be checked for anti-endomysial antibodies or tissue transglutaminase.

- Urine testing for blood is important in the examination of patients with IDA as approximately 1% of patients with IDA will have renal tract malignancy. Further renal tract evaluation with ultrasound is recommended if haematuria is found, followed by intravenous urography and/or CT scan as necessary.

- Rectal examination is seldom contributory, and, in the absence of symptoms such as rectal bleeding and tenesmus, may be postponed until colonoscopy.

- All the groups mentioned above need OGD plus D2 biopsy (if coeliac antibodies are positive or not done and colonoscopy/CT colography. Colonoscopy has advantages over CT colography for investigation of the lower GI tract in IDA, but either is acceptable. Either is preferable to barium enema, which is useful if they are not available

- One or the other pathway only abandoned if gastric or colon cancer or coeliac disease diagnosed. Investigation with OGD and colonoscopy/barium enema reveals a cause in 2/3 of the patients. It is reassuring to know that iron deficiency does not return in most patients in whom a cause for IDA is not found after upper GI endoscopy, small bowel biopsy and barium enema.

- Further direct visualisation of the small bowel is not necessary unless there are symptoms suggestive of small bowel disease, or if the haemoglobin cannot be restored or maintained with iron therapy .Wireless capsule endoscopy is the investigation of choice in such a scenario. If a small bowel lesion is identified, push or balloon enteroscopy can be used to treat the lesions. Many lesions detected by both enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy are within the reach of a gastroscope and repeat OGD should be considered prior to these procedures. Small bowel radiology is rarely of use unless the history is suggestive of Crohn’s disease.

Discuss iron replacement treatment?

- Oral replacement- This is achieved most simply and cheaply with ferrous sulphate 200 mg twice daily although ferrous gluconate and ferrous fumarate are as effective and may be better tolerated. A liquid preparation may be tolerated when tablets are not. Ascorbic acid enhances iron absorption and should be considered when response is poor.

- Parenteral replacement- should be used when there is intolerance to oral preparations or non-compliance.

Discuss the parenteral iron preparations?

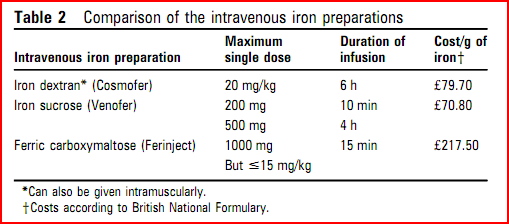

- Intravenous iron sucrose is well tolerated Bolus IV iron sucrose (200mg iron) over 10minutes is licensed and more convenient than a two hour infusion.

- IV iron dextran can replenish iron and Hb levels in a single infusion, but serious reactions can occur (0.6-0.7%) and there have been fatalities associated with infusion. However, it can be given via IM route when venous access is problematic.

- Ferric carboxymaltose (Ferinject)- The principle advantage of ferinject is the abbreviated duration of infusion, without the need for a test dosed15 min compared with 6 h with Cosmofer (consisting of a 15 min test dose, 45 min observation, 4 h infusion, then 1 h observation). Although drug costs are higher, length of stay in a day-case or primary-care facility is reduced

IV iron sucrose and sodium ferric gluconate are rarely associated with severe allergic reactions and deaths, and are better tolerated than iron dextran even at high doses and thus are preferred.

How do you calculate the dose for parenteral iron therapy?

Dose in mg of iron= body weight in kg X (12-present Hb. X10) X 0.24

Add to this a depot of 500mg.

Link to calculate the iron dose

IV iron sucrose can be administered at 200mg weekly for five weeks. Alternatively, iron sucrose can be given at 500mg IV (in 250cc of NS) over four hours once weekly for two weeks.

Discuss follow up of IDA?

Once normal, the Hb concentration and red cell indices should be monitored at intervals. We suggest 3 monthly for 1 year, then after a further year, and again if symptoms of anaemia develop after that.

Ref